Is UX research about “de-risking” design?

A recent conversation I had about UX research centred on whether such research is to help designers predict eventual outcomes of design interventions, or whether its role is to “de-risk” UX or business ideas.

They were keen to frame research as a way of lowering risk to the business. This applied both to design validation as well as exploratory research. The term “prediction” sat badly with them. Although they didn’t deny that “de-risking” was inherently predictive, to call it prediction seemed too technical in some way, and placed too much emphasis on being “correct”.

It also sounded to me like they thought the idea of prediction was deterministic thinking. But what I mean when I talk about prediction in design is “probabilistic thinking”.

Coincidentally, my favourite researcher and user of XKCD comics, Danah Boyd has just posted about what I mean by this (albeit in the context of AI, but that’s not relevant).

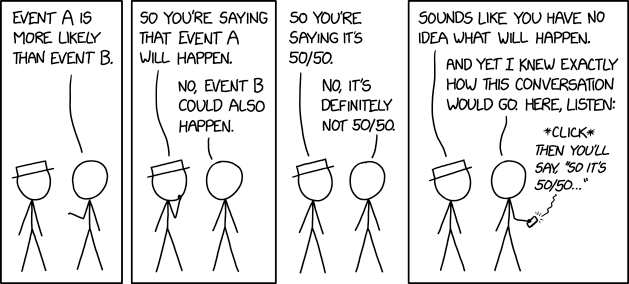

You could bet money against these people, but you have to consider the probability of them paying up. XKCD

If you read what she says in the article, it aligns with my view that research should be checking whether what we said about a given intervention tends to happen.

For example, if our hypothesis is that because Sainsbury’s SmartShop is about speed in buying and checking out as soon as possible, then intervention X (a deterministic thing) which increases the speed of use will bring about about more/less of something the business is interested in (acquisition, retention, conversion, or lowering cost to serve). So over time and multiple tests of different interventions based on that hypothesis, you can give that hypothesis a rough probability of its predictive powers. It might be weak (or irrelevant) or it might be strong (and worth doing more of or drilling into).

This means designers are free to think creatively across projects, but with what Boyd calls “guardrails” set up by the activity of research so that design isn’t working simply as a feature factory. SmartShop might be about love of gadgetry and tech, and not speed, for example. But the mission is to posit that and then work out which is the more accurate predictor. Having multiple opposing hypotheses to test is a good idea.

“De-risking” sells research short

So perhaps I’m saying that most business environments have lots of deterministic thinking (just look at those roadmaps!) but very little emphasis on refining or attempting to be less wrong about why or even whether what we say will happen in fact results in what we expect. “De-risking” is OK, but I see that as meaning it’s just a check to make sure customers “get it” or not.

Fundamentally, it’s not enough to know that people like or dislike, or even want things. Design is about why people use Favourites, or why they amend orders in the online shopping process, choose credit, use Nectar points, or even shop in a store when they could do so online. When research is all about collections of facts grouped by “personas” or “missions” to make contradiction palatable, the designer is left with no agreed reference with which to interpret the results. And so the feature factory grinds on in the hope that it gets more winners than losers because some people once said they’d like a particular thing.

As a footnote to this, I think I find it hard to explain these concepts to other designers because my idea of a design hypothesis (or even design itself) is not the same as theirs. This in turn seems to be because they don’t see design ideas as being about probabilities. They see them as deterministic certainties, but with no guardrails to run on.

[…] and obvious solution, so when the design team starts pushing back and asking for time to do additional research, it sounds like a waste of time. Or worse, it might sound like the design team is actively trying […]